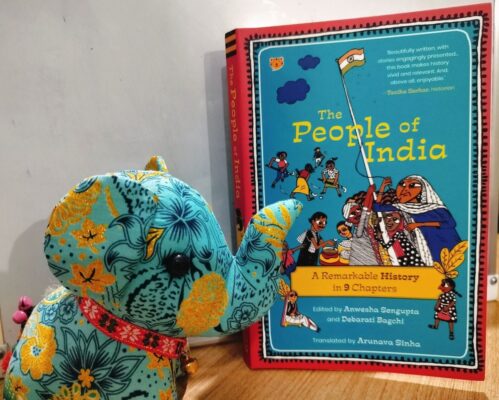

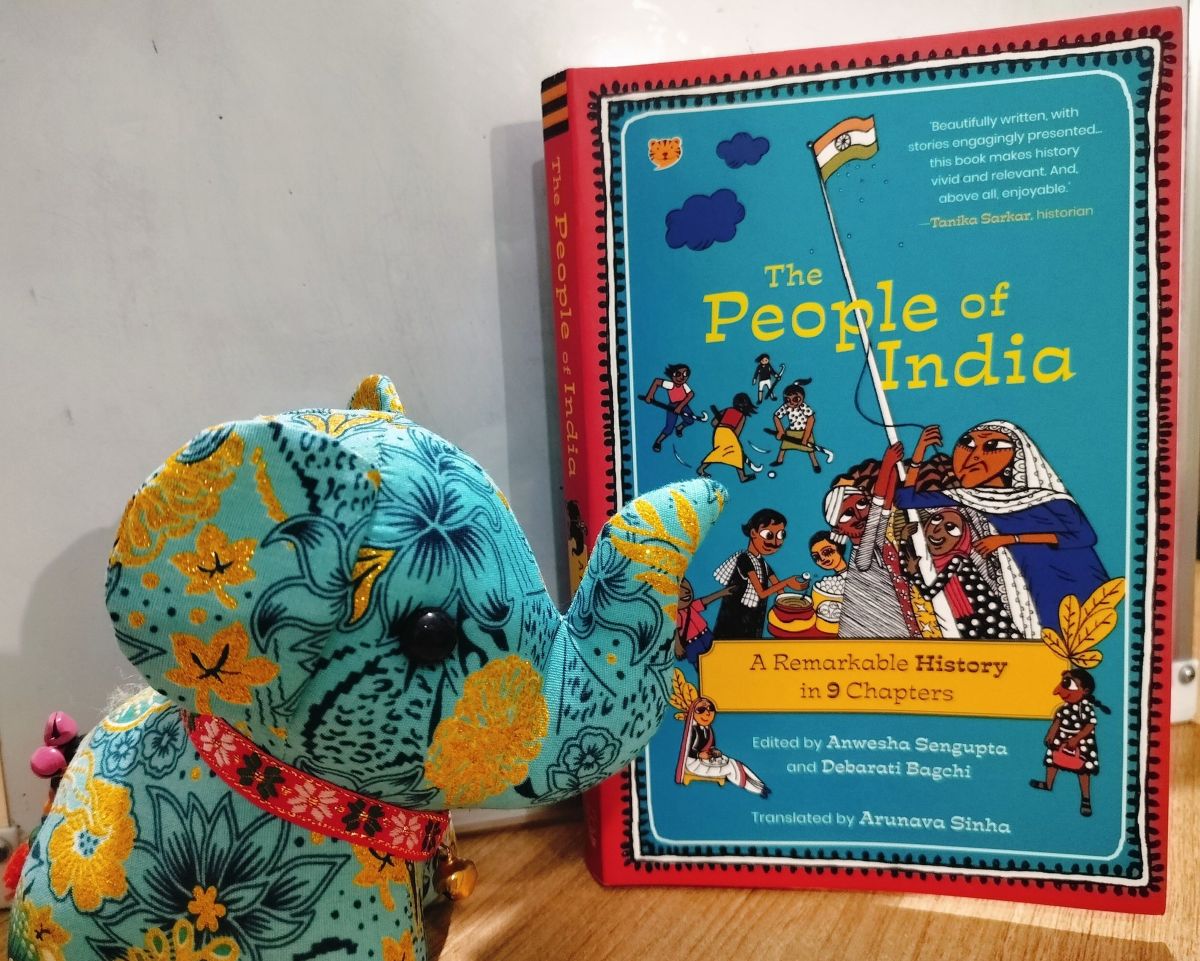

Title: The People of India: A Remarkable History in 9 Chapters

Edited By: Anwesha Sengupta and Debarati Bagchi

Translated By: Arunava Sinha

Cover Illustrator: Kavita Singh Kale

Cover Design: Maithili Doshi Aphale

Type: Paperback

Genre: Non-Fiction/History

Publisher: Talking Cub (an imprint of Speaking Tiger Books)

Length: 265 pages

Age group: 11 years onwards

This is the first translated book I’ve picked up this year, and it truly drew me in. Originally written in Bangla, the book is titled Etihasir Hathikhori, which translates to First History Lessons. In Bengal, the ritual of hathikhori (holding one’s first chalk in hand) marks a child’s initiation into writing. The title itself carries that symbolism: history being introduced to young readers as a first step, not as something distant or dull.

For most of us, history in school is synonymous with exams, marks, and rote memorisation. Rarely do we encounter history as something alive, curious, and engaging. That’s what makes this book refreshing; it’s written in an approachable way for middle-grade readers, using simple language while opening up deep perspectives.

The introduction offers much-needed clarity on why these topics were chosen and how the ideas came together. One striking example is the way partition is explained. Partition was not just a political division—it required practical calculations of which assets went to India and which to Pakistan. This is narrated through vivid, unusual lenses. For instance, in a district of Bengal where the power of landlords was measured by the number of elephants they owned, one government-owned elephant, Joymoni, stood at the heart of a partition dilemma: which country should it belong to? Such storytelling makes complex history tangible and human.

Another example is how Cyril Radcliffe, the English lawyer appointed to draw the boundary line, used rivers like the Padmavati, Mathabhanga, and Ichamati as borders. But rivers change course. So would the border shift too? Questions like these make you pause and reflect not only on geography but also on the very concept of boundaries. What does a boundary mean to you? Is it geographical, philosophical, or personal? And do others see it the same way?

The book also highlights how partition disrupted everyday life in small but profound ways—such as people struggling to stick to their staple foods amid the chaos. These details, often lost in grand narratives, reveal the tenderness, the empathy, and the resilience of ordinary people. Another significant aspect is how partition pushed many women into the workforce. Families torn apart had no choice but for women to step into roles outside the home. In this way, tragedy also became a turning point, a ray of independence for many.

The book goes beyond partition, too. One chapter examines how languages shaped the nation, raising questions about whether languages bind or break a country, how majority and minority languages played out, and how states were split along linguistic lines. While this chapter felt more like straightforward reporting and a bit dry for young readers, the subject itself is vital.

The chapter on war also reads somewhat monotonously, but the scattered verses and reflective questions act as breathers. It explores how wars at home and abroad shaped India, the liberation struggles, and even how conflicts in one corner of the world ripple to the other. It left me reflecting: what is really gained from war, and who bears the losses? A question painfully relevant in today’s times.

The section on rivers was especially thought-provoking. Can humans truly claim control over rivers—ever-changing forces of nature? History shows us how kingdoms tried to bend rivers to their will, but eventually withered away, while rivers continued to flow. The chapter also traces how rivers shaped trade, connected with railway routes, and became central to questions of water-sharing through dams.

Another standout is the chapter on tea, which uncovers the lives of workers in tea gardens—their struggles and contributions hidden beneath the multi-billion dollar industry their labour sustains. Similarly, the chapter on food goes beyond “what people ate” to explore prejudices around diets, gender roles in cooking, the symbolic role of fasting, and how hunger itself became a form of protest.

The clothing chapter ties attire to power, politics, and identity—priestly robes, colonial influence, khadi and the anti-British movement, and how women’s bodies and clothing were shaped across history.

Taken together, the book offers a multidimensional perspective on the people of India, their histories, and the ways the past still speaks to the present. While the anecdotes in the first chapter and a few other sections keep readers hooked, there are parts that lapse into drier, textbook-like narration, which may feel heavy for children aged 11 and above, the target audience. However, for history enthusiasts and reflective readers, this book is valuable. It blends fresh perspectives with layered storytelling, making us not just learn history but also question identity, belonging, and the connections between past and present.

If you enjoyed the review and are a history enthusiast, you can order the book from Amazon (kbc affiliate link),

CLICK & BUY NOW!Disclaimer: Seethalakshmi and her daughter are a part of the #kbcReviewerSquad and received this book as a review copy from the publisher via kbc.